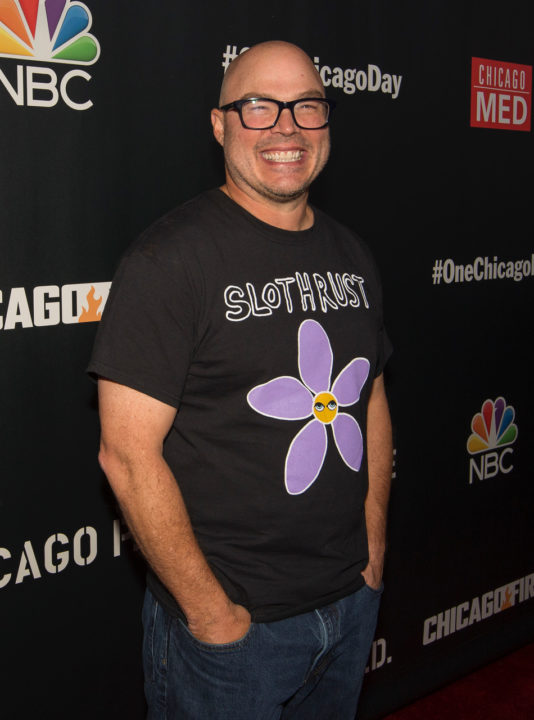

Spotlight: Derek Haas

The world of Wolf Entertainment is full of creative minds that make each facet of the shows we love come to life. In our new interview series, Spotlight, we talk with the masters of craft—from members of the production team and designers who lead marketing to showrunners that bring storylines to the screen week after week.

Whether you’ve been a fan of Wolf for one year or ten, chances are high that you’ve come across the work of Derek Haas. From creating and serving as the showrunner of “Chicago Fire” to developing and executive producing every series within the #OneChicago world, Derek’s creative power is undeniable. We had the chance to chat with him to learn more about his career, how producing and writing complement one another throughout the creative process, and gather some advice for aspiring writers.

We all know showrunners are the anchor of any television series. Can you talk a bit about your role as a showrunner? What does your day to day look like?

When we make this television show, we essentially have to make 22 to 24 movies every eight days; every eight days is a new production. As a showrunner, I work with the writing staff, actors, and so forth. I’m in charge of making sure the train stays on the tracks.

If I’m in LA, then my day usually finds me reading the outlines or scripts that come my way or in the writers room working with the writing staff on the ideas for story arcs, half-seasons, or individuals episodes. If I’m writing the episode myself, then I’ll craft the board and consult my head writers, Andrea and Gilvary.

Other days I’ll be talking to the network or studio about an episode or script, viewing an episode in post-production and seeing where we can improve it, or checking in with production to make sure everything is going smoothly.

If we’re in production on an episode I wrote, then I’m usually on set working with the director and actors to make sure we’re hitting the tone and meaning of each scene.

Prior to the Chicago shows, you mainly wrote films and novels. Can you tell us a bit about your transition into TV? How does it differ from writing for other mediums?

I got a call from Dick Wolf saying that he wanted to do a television show about firefighters, and I had just come off doing an independent movie with my then partner Michael Brandtand we thought, “Oh, let’s just write this pilot and get back to our lives.” I had no idea that it would be the next eight years of my life.

When thinking back, we were excited about the opportunity to work with Dick. When we realized that we could set the show in Chicago (a town I didn’t know a lot about at the time) it started to click. We rode around with the Chicago Fire Department for three weeks just taking it all in, and when I saw the real life drama of working in a busy house where bells are going off mid-conversation—it was incredible. These bells go off and they don’t tell you much at all, you leave the firehouse not knowing what kind of call you’re going to run up on. It could be man down from unknown causes, someone stabbed, fighting, and so on. The experience of riding up on something and having to improvise made for an exciting and compelling story to tell.

Now, going back to the question, the main difference between television writing and other mediums is that it never stops. You can write a book or a movie and you have an end date in mind. When writing for television, you have characters that you will live with—they’ll be inside your head—for many years. It’s the longest relationship outside of marriage, a roller coaster that never stops. You just have to hold on with both hands.

Beginning with “Chicago Fire”, you’ve now seen many a series and spin-off in the #OneChicago universe. How do you find the tone of Fire has evolved as it has become increasingly integrated with additional shows over the years?

Tonally, I don’t think it’s very different today than what it was like in the pilot. It’s always been centered on the family in this firehouse. They all have the same trials and tribulations of any other family, and they always have each other’s backs—that central motif has been alive for eight years now.

During season one, we found that the firefighters were always crossing paths with police or hospital staff, and Dick said, “Why don’t we just build other shows around these first responders?” What’s great is that we now have an expanded sandbox to play in with the growth of the world of Chicago.

As a writer and producer, do you need to regularly bring a multi-faceted outlook to your work? How do the two mindsets complement one another and do they ever clash?

As a producer, you learn that what you picture in your head and what you can make on the screen aren’t always the same thing. You learn as you gain experience that you need to adapt your writing to the strengths of an actor, director, production details—even down to where the sets are. I’m always amazed at what our cast and crew can pull off with regards to what we come up with, but we do always try and write towards strengths.

In fact, the characters start to absorb certain characteristics of actors, and we exploit relationships off-set and bring them into the on-set scripts. You can’t fake these friendships that you see on-screen, and it accrues to our benefit.

The two mindsets really only clash when there’s a budget problem or a length of schedule problem. Our imaginations can get the best of us. I could see an episode with a giant plane crashing into Michigan Avenue, but that doesn’t mean we can pull it off in eight days.

You wrote this year’s Chicago crossover event Infection, can you talk a bit about that process? What was the biggest challenge in creating the crossover?

This one was unique in that we weren’t sure we were even going to do one in the first ten episodes, but then Dick led the charge in saying that we were going to do it in the first five—it was too important of a statement to let it slide until January.

He had the idea to create a story around weaponized bacteria. I created the overarching story of all three with Dick, and then I wrote the first hour, which belonged to Fire. There is always a challenge because you have three of everything and you have to make it one story with one look and feel. This was the most intricately plotted crossover as well. Actors love it because they get to work with the casts from the other shows, which is always fun.

It’s apparent from watching the crossover and social media that the casts of all three shows are friends off camera. Can you talk a bit about the culture on these sets? Was it something you and the producers worked to create or did it happen organically?

It all happened organically, but as time goes on, you realize that you’re not just casting a person that fits the role, it’s about how they fit within the family of actors of the show. It started with Eamonn Walker and David Eigenberg who are both veteran actors. They have a leadership quality that cannot be taught in terms of work ethic, responsibility, and generosity. When we brought in the three stars at the beginning—Taylor Kinney, Jesse Spencer, and Monica Raymund—they all looked to Eamonn and David, and they served as the perfect role models in every single way for our three leads.

I do think that playing first responders in a way helps that off camera camaraderie. We have first responders walking around sets, real firefighters working as consultants, and so forth. It’s hard to be a diva if the guy standing next to you might be running into a burning building tomorrow.

What advice would you give to writers eager to enter the entertainment industry?

I think it’s so important to have a great ear for dialogue and the way that people actually talk. There’s such a massive difference between how it reads on the page versus how it sounds when actors perform it. It can sometimes feel inauthentic or forced—people don’t talk in complete sentences and not every line is carefully thought out.

We read so much inauthentic dialogue, so when you have a good ear and you can put that on paper, that’s what makes you stand out. Dick feels the same way. He always asks, “How is their dialogue?”

It has to be powerful, and having a great ear for dialogue is not something easy to teach.