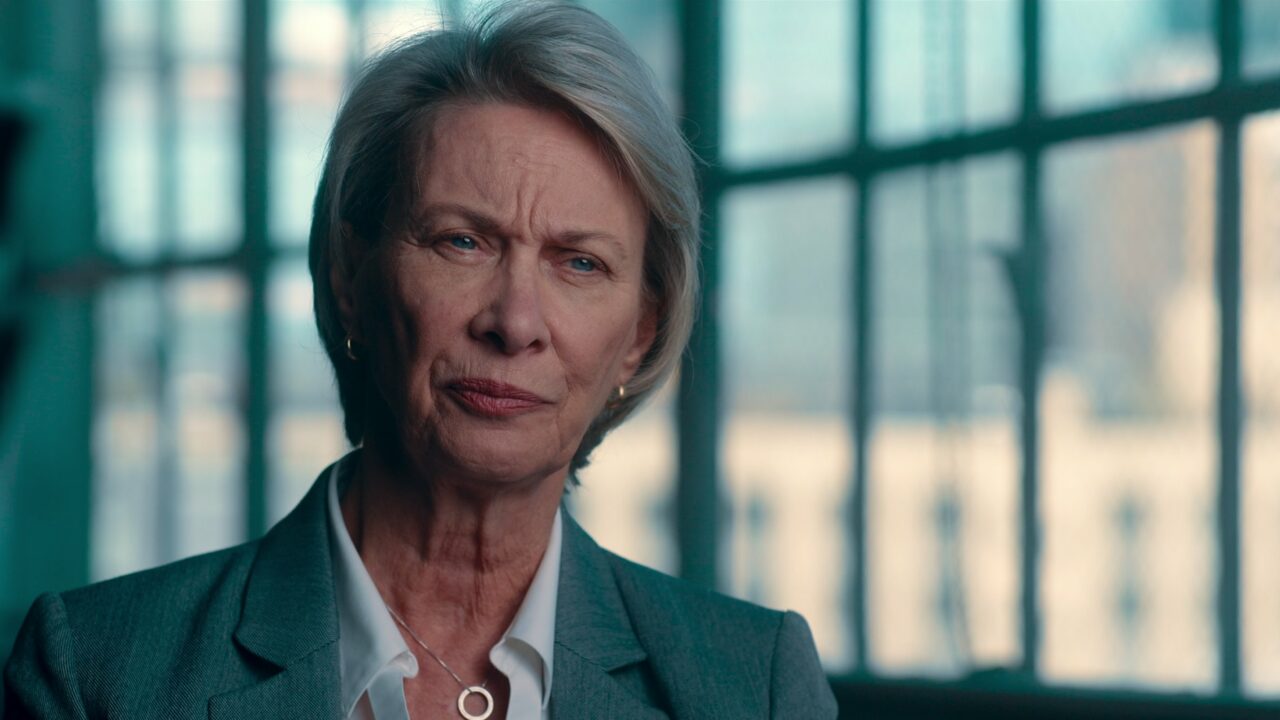

Spotlight: Barbara Butcher

In her decades of experience as a medicolegal death investigator in New York City, Barbara Butcher faced death head-on. Now, she’s back on the job as a part of Homicide: New York on Netflix, a new show from Wolf Entertainment that takes viewers behind the scenes of homicide cases in the city. We talked with Barbara about her long and storied career, what she’s learned from her time in this field, and what it was like to get back into action on Homicide: New York.

Q: How did you become interested in pursuing a career as a death investigator?

A: As a kid, I loved mysteries, and I also had a fascination with death. My parents got me a dissection kit, and neighborhood kids would bring me roadkill from the streets — I liked to figure out how the creature died, whether it was a squirrel or a snake or anything else. I was a very strange child I suppose, but I just liked figuring things out.

I began my career working in healthcare, first as a physician assistant working in surgery and preventive medicine, and then as hospital administrator. At that point, drinking caught up with me. Once I got sober in a 12-step program, I attended EPRA, the employment program for recovering alcoholics. They gave me a few personality tests, and from that they determined that my career should either be as a coroner or a poultry veterinarian. I said, well, I think I’d prefer the dead people, thanks. It all harkened back to when I was a kid figuring out mysteries.

Q: How did you get your first job in this field?

A: My counselor suggested that I call the person who I thought had the best job in the world and ask them for an interview, so I called Dr. Charles Hirsch, New York City’s chief medical examiner. He invited me to the office for an interview, and it just so happened they had a job opening for an investigator with the NYC Office of Chief Medical Examiner, which they offered to me. It was a dream come true. I trained on the job, and then I went to courses at the NYPD and the FBI. I was hooked. This was the coolest, most interesting, most useful job in the whole world. Getting justice for people — what could be better?

For the first 11 years I worked as a death investigator, I did something like 680 homicides and 5,500 scene investigations. Each and every one told a story, and each one was fascinating. I got to see not just how people died, but how they lived. You have unfettered access to a person’s home — you can look at everything, you can touch everything, you can figure out everything about their lives through their deaths. I just loved it. I got to do something good too, while I was having fun. I got to help families who needed answers, and I got to get justice for people who could no longer speak for themselves. I could speak for them.

Q: What does a death investigator do?

A: When most people think about medical examiners and coroners, they think about the autopsy. But those are done by forensic pathologists — those are the people who are in the room doing the dissecting. They can’t drop everything and run out to a murder, so you have death scene investigators. These are people, usually with medical backgrounds, who are responsible for defining the context of the death. For example, if you have a gunshot wound and you’re doing an autopsy, the cause of death is a gunshot wound, but what’s the manner of death? How did it arise: a homicide, suicide, or even an accident? It was my responsibility to go to the scene and determine that context.

I say in the show that the scene belongs to the police and the body belongs to me, but the reality is that the dead body is what makes it a scene, so therefore it’s all technically mine. I explored the scene thoroughly with the police and the crime scene investigators. Upon returning from the scene, I would make a report to the medical examiner and present photographs, measurements, and anything else, so that they could do an autopsy and gather full knowledge of how the death occurred.

Q: What is something that people would find surprising about this line of work?

A: It’s not surprising that it’s soul crushing. You have to learn detachment so that you don’t become emotionally crippled from shutting down against all the grief and terror and pain. What may be a surprise to people is how satisfying it is. If you’re a curious person and you have to solve the puzzle and have to get answers, it’s enormously satisfying to be able to go and figure things out. Ultimately, even though we are working for justice and for the victim, we’re mostly working for the families — they’re the ones that deserve answers.

Q: What was it like to work on Homicide: New York?

A: When I first went in, I had some trepidation because I had just finished writing What the Dead Know, my book about my cases and my adventures and my life. That took a lot out of me emotionally — sometimes I would write things and just cry because I felt those feelings again. I thought, well, I’ve gotten all of that out of me, I can go in there and talk about these cases again and it’ll be fine. Well, that wasn’t the case. Speaking out loud about the lives I saw destroyed and what it meant put me in a melancholy state.

On the other hand, there was a great sense of camaraderie. That’s one of the things I miss most about my job, the camaraderie among people who do this kind of work: the police, firemen, death investigators, and EMTs. It felt so good to be a part of that team again, that special group of people who work on the edges of life, where things are chaotic and crazy. It’s a special group, and I loved being back in it, even for just a little while.

Q: What helped you work through the difficult feelings that arose as you were revisiting all of this information?

A: The only way I know how to move through the sorrow and the grief for people who suffered is by doing a gratitude practice. When I’m walking down the street, I remind myself of how fortunate I am to be able to walk, to breathe the air, to see all the buildings around me. I play a little like a kid, you know how children skip down the street and they get absorbed by everything they see. Doing that and being grateful for what I’m experiencing is probably the most effective thing I know, because in describing to myself what I see, hear, smell, and think, I’m reminded of how lucky I am to be able to have all that to experience this and that there is a purpose for what I do.

Q: What is your favorite episode of Homicide: New York?

A: It would have to be the episode where we covered the case of the Baby-Faced Butchers, Daphne Abdela and Christopher Vasquez. These two troubled children, only 15 years old, committed one of the most vicious, brutal murders I’ve ever seen. The irony of youthful innocence destroying life has stuck with me — the fact that children can kill, and I still don’t know why, haunts me. I would love to talk to the perpetrators and understand what happened. That’s one of the perplexing parts of the job — sometimes we just don’t know why. Only in revisiting it can we try to make some sense of it.

Q: What do you hope that viewers take away from the show?

A: I hope that people take away that every single life counts. When you see on the news that a man was killed in the subway, instead of thinking oh, that’s awful, I’m scared, this city’s going to hell, maybe you’ll think instead about how his mother, his girlfriend, his brothers and sisters, are awash in grief and sorrow that they’ll never see someone they love ever again. Maybe that’s too much to think about, but I think it would be great if viewers could get just a hint of that, to understand even a little about what murder really does to society, and to all of us. Every single life is a universe unto itself. You may have heard the expression that one death is a tragedy, and 10,000 deaths is a statistic, but that’s not true — nobody is a statistic. Each life is important. Each life can change the world. I think I got to see that in spades.

Stream Homicide: New York now on Netflix.